While clinicians judge the success of periodontal plastic surgery based on aesthetic and functional criteria, patients often evaluate it based on their postoperative experience at the donor site, including pain intensity, uncontrolled bleeding, and chewing discomfort. Therefore, the graft and its harvesting method are critical for both clinicians and patients, influencing both outcomes and postoperative recovery. Biomaterials are often less reliable than autologous grafts, making the use of the tuberosity particularly attractive 1 . Harvesting from the tuberosity is almost free from hemorrhagic and painful complications, and when used correctly, it ensures lasting aesthetic and functional results.

PROPERTIES OF TUBEROSITY CONNECTIVE TISSUE GRAFTS

♦ Structural aspects. In the tuberosity, the lamina propria and the underlying connective tissue have almost similar structural characteristics. Composed of a dense and highly cross-linked collagen network, the tuberosity graft undergoes minimal remodeling, providing a stable augmentation material over time 2,3. It may sometime show a tendency to expand when provided in large quantities 3,4. For recession treatments with tuberosity material, only the necessary volume should be supplied to optimize the graft’s visual integration, unlike palatal material which tends to remodel and contract.

♦ Vascular characteristics. The vascular network of the tuberosity is reduced compared to the palate 3. This anatomical feature restricts the tuberosity graft to strictly buried uses. Any exposure outside the tunnel’s limits risks necrosis.

♦ Keratinization potential. A keratinized tissue is characterized by the accumulation of a highly resistant reticulated protein, keratin, within its epithelial cells. This protein accumulation offers increased resistance to environmental stresses, be they mechanical, thermal, chemical, or microbiological. A tuberosity graft has the potential for trans-flap keratinization5, meaning it can induce keratinization in non-keratinized tissue or increase keratinization in already keratinized tissue, under certain conditions. This biological induction mainly occurs if the flap above the graft is thin, whereas a thick flap seems to block this process. While this keratinization phenomenon is desirable in non-aesthetic areas for added reinforcement, it must be avoided in visible areas to prevent irreversible tissue discoloration.

POSTOPERATIVE OUTCOMES OF TUBEROSITY HARVESTING

The postoperative outcomes of tuberosity harvesting are minimal 6,7. Due to the low vascularization of the tuberosity, hemorrhagic risks during harvesting and the healing phase are extremely limited, unlike palatal harvesting. In terms of pain, tuberosity harvesting is relatively unnoticeable, whether done via flap or gingivectomy. The healing mode, whether by primary or secondary intention, does not seem to affect postoperative outcomes. Several factors explain this, including lower innervation of the region and its anatomical position outside the tongue’s exploration zone and food impaction.

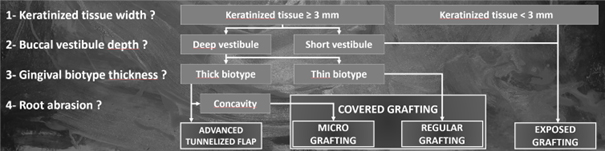

Fig. 1 : decision tree for a treatment concept associated with tunneling. (Tunneling: A Comprehensive Concept in Periodontal Plastic Surgery. Ronco V., Quintessence Publishing International).

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

In a treatment concept published in 2021, grafts associated with tunneling are divided into two categories: buried and exposed grafts 8. As shown in Fig. 1, clinicians can choose a graft strategy based on well-defined and easily identifiable clinical criteria: residual gingival height, vestibular depth, biotype thickness, and depth of non-carious root lesions. These grafts are typically performed with connective tissue grafts of palatal origin. However, tuberosity grafts can substitute for or combine with palatal grafts in certain indications.

For covered grafting, connective tissue grafts can be either continuous or segmented.

A conventional graft, i.e. continuous, spreads buccally and proximally to the treated teeth. The tuberosity cannot provide a graft long enough to replace palatal grafts in these indications but can be used in forming a double-layer graft. This variant of the conventional graft combines a palatal origin main graft with an additional tuberosity graft locally, leveraging the overall bilayer graft characteristics. As depicted in Fig 2, this construction takes the best of every connective tissue characteristic to address a specific clinical issue.

Fig. 2-1 : RT1 recessions affecting mandibular incisors are not problematic in their current state due to the relatively thick gingival biotype. However, an orthodontic treatment is planned. The preview of orthodontic movements shows significant buccal displacement of the incisors and a strong vestibulo-version. Therefore, the orthodontist requests biotype reinforcement in the incisal sector before starting the treatment.

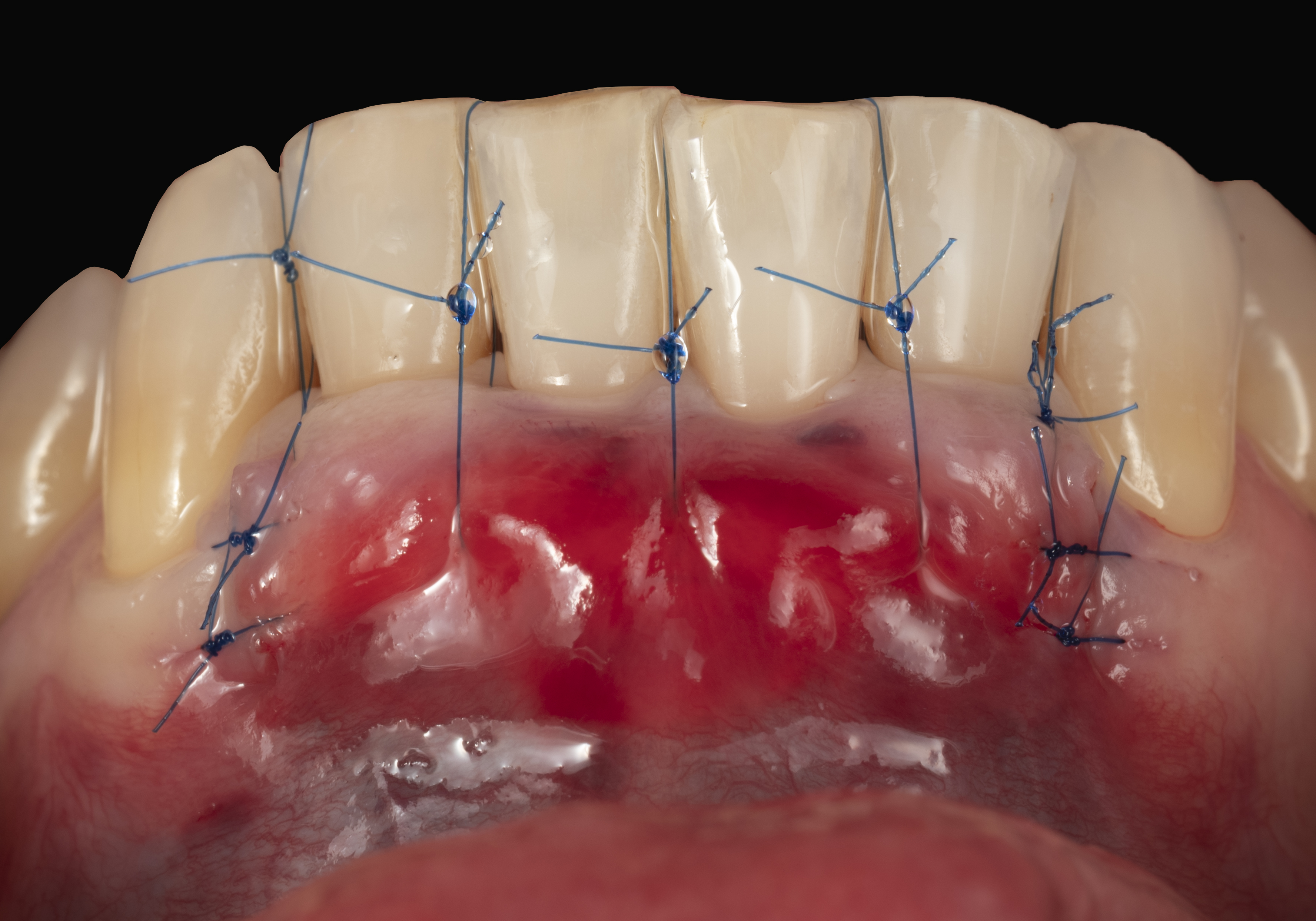

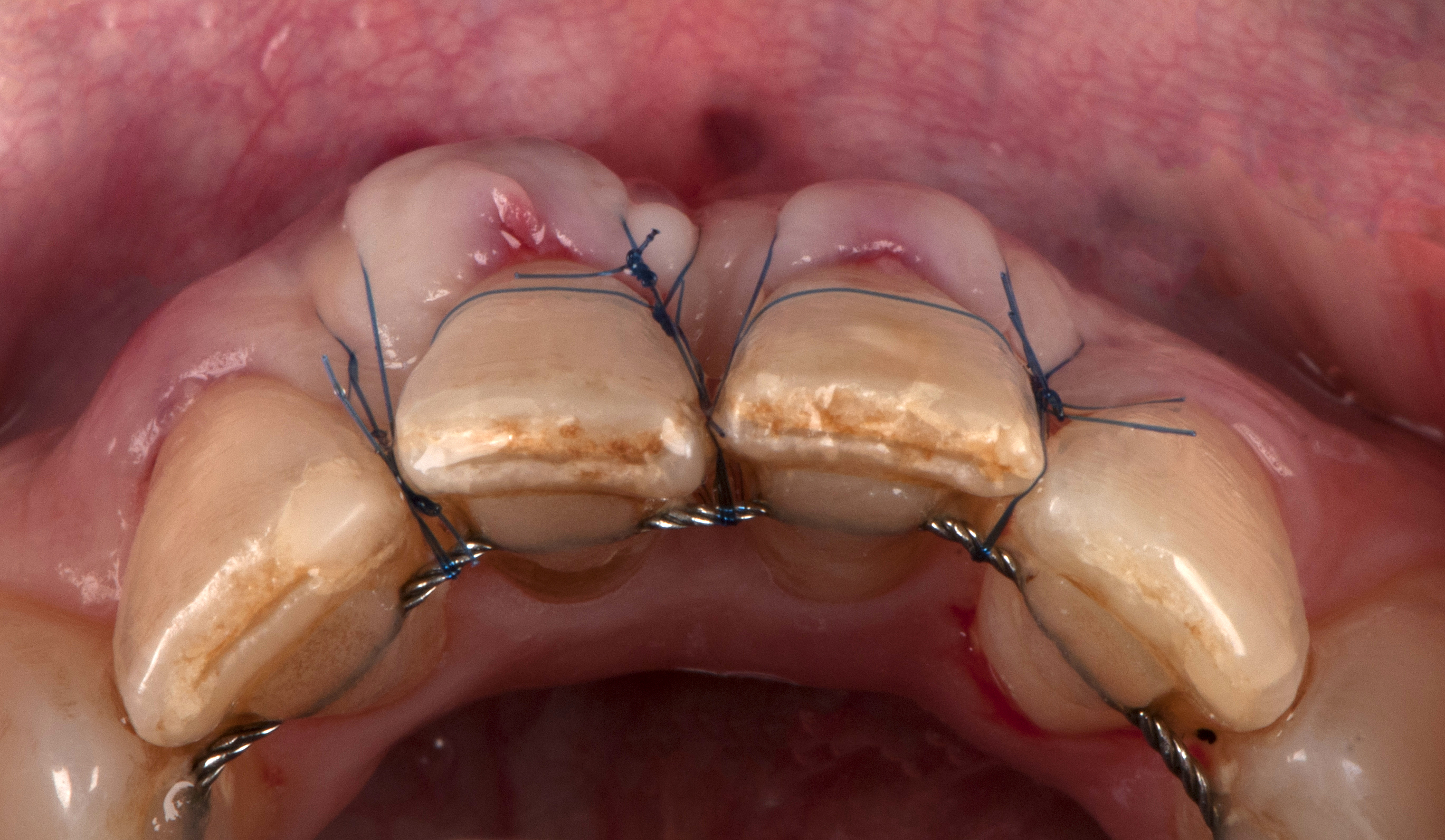

Fig. 2-2: tunneling is typically performed via the endosulcular route. However, when the recessions are small or nonexistent, this procedure is difficult to perform and the risk of tearing the flap is high. Therefore, two buttonholes are added, allowing for a “retro” tunneling from apical to coronal10.

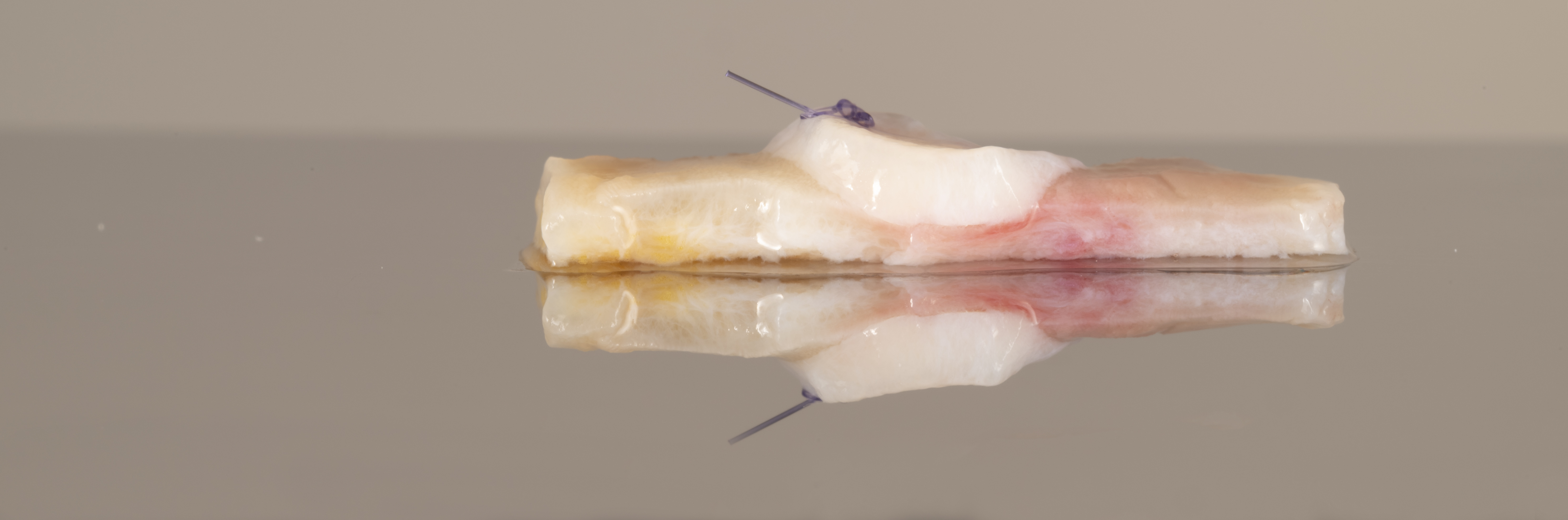

Fig. 2-3: in this particular case of biotype reinforcement before orthodontics, the combination of a palatal graft with a tuberosity graft is interesting. The assembly is performed using a resorbable suture. The tuberosity graft is positioned in the center to thicken and hyper-keratinize the biotype in the region of the central incisors, which are notably more prone to recessions.

Fig. 2-4: the lateral buttonholes are also essential for graft insertion. It would indeed have been impossible to insert the graft via the endosulcular route.

Fig. 2-5: at the end of the procedure, the combination of the double-layer graft and the tunnelized flap is positioned and secured coronally to the cementoenamel junction. The buttonholes are closed.

Fig. 2-7: condition after complete healing (3 months). The thickening of the gingival biotype is such that orthodontic treatment can begin without periodontal risk.

Conversely, a micrograft is narrower than the buccal aspect of the treated tooth, the treatment philosophy being based on tissue economy and aesthetic optimization. The clinical case shown in Fig. 3 illustrates how tuberosity grafts can advantageously replace palatal grafts in this indication.

Fig. 3-1: in a context of thick gingival biotype and low smile line, RT1 recessions have developed in the anterior maxillary region. Non-carious lesions are present on the central and lateral incisors.

Fig. 3-2: the use of a continuous graft, extending both buccally and proximally to the treated teeth, presents significant aesthetic and morbidity disadvantages when the gingival biotype is initially thick. In this scenario, global thickening of the gingiva, especially at the base of the papillae, with a continuous graft is not desirable as the risk of disharmonious over-thickening is real. Additionally, this treatment approach requires large palatal areas to be harvested, increasing the intervention’s morbidity. Four micro-grafts are harvested from the tuberosity. The photographs show the grafts in their “raw” state before reshaping. Once reshaped, they will fit perfectly into the concave root areas.

Fig. 3-3: post-operative views. The combination of the micro-grafts and the flap is moved, immobilized, and applied to the teeth beyond the cementoenamel junction using the “Belt & Suspenders” suture concept (8). The precision of these suspended sutures prevents any chaotic exposure resulting from postoperative edema. This level of precision is essential for the revascularization of the tuberosity micro-grafts.

Fig. 3-5: condition at 3 years. Root coverage is complete. The tuberosity micro-grafts, used as space maintainers, are not intended to thicken an already thick gingival biotype but to compensate for concave root areas. Consequently, the occlusal view shows a harmonious and continuous biotype. There is no unsightly increase in surface keratinization, as the initially thick gingival biotype acts as a barrier, and the volume of provided tuber material was minimal.

For exposed grafting, a continuous graft extends over the entire width of the operated site, intentionally exposed at gingival recessions level while buried elsewhere. Partial coverage of exposed areas by lateral displacement of peripheral tissue is sometimes possible, depending on local conditions, to lower the risk of ischemia 9. However, in complex gingival reconstruction cases, a single intervention may not always achieve optimum results, and a second stage may be necessary for desired coverage and thickening. The clinical case shown in Fig. 4 demonstrates how the tuberosity can play a strategic role in the second stage of the procedure.

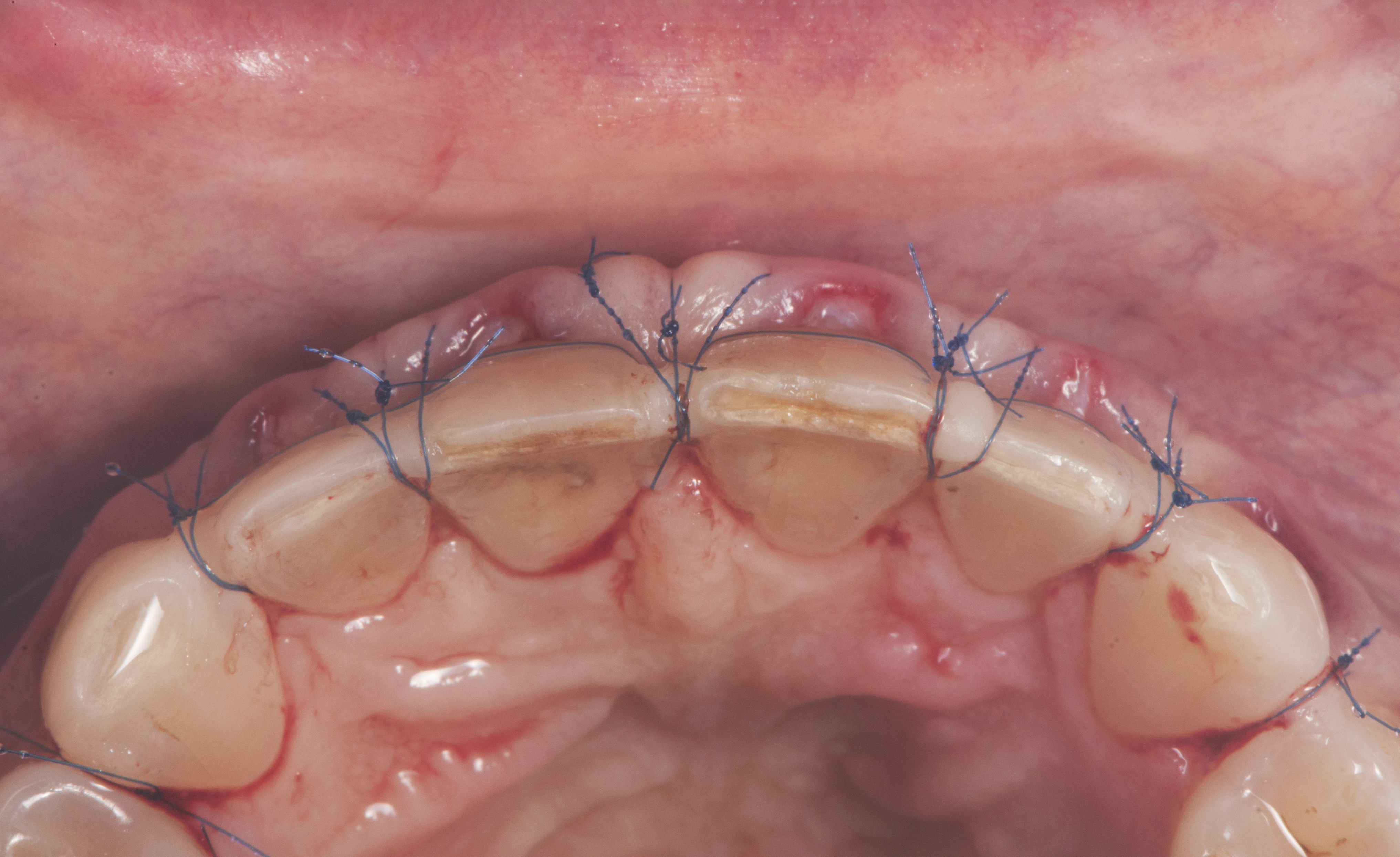

Fig. 4-1: central and lateral mandibular incisors present with RT2 recessions. The vestibule is very shallow. The roots are projected buccally in relation with their positioning and version.

Fig. 4-2: a palatal connective tissue graft is intentionally exposed. The transfixation of the tunnellized flap with the underlying graft by the “Suspenders” sutures precisely sets of the graft’s exposure degree. In this case, it is not possible to close the tunnel laterally due to the root projection, the contiguity of the recessions, and the graft’s thickness.

Fig. 4-3: healing at 2 months. Root coverage is complete on the right central incisor and only partial on the left central incisor, with about two-thirds of the recession covered. The achieved root coverage results exclusively from gingival creation by secondary intention healing. The buccal vestibule is deepened. Benefiting from the first surgery outcomes, a second intervention is planned to improve and durably stabilize the results.

Fig. 4-4: after tunneling at central incisors, a tuber graft is placed in the tunnel. The choice of a connective tissue graft originating from the tuberosity is justified by its potential for trans-flap keratinization and minimal dimensional remodeling over time. The low postoperative complications of a tuberosity harvest also contribute to this choice.

Fig. 4-5: the tuberosity graft is completely buried. The combination of the graft and the flap is moved, applied against the teeth beyond the cementoenamel junction, and immobilized using the “Belt & Suspenders” suture concept.

Fig. 4-7: condition at 3 years. Root coverage is complete. The buccal vestibule is deepened, greatly improving the site cleanability. Long-term tissue stability is also ensured by creating a thick biotype and strong keratinization. In this regard, the tuberosity graft significantly contributes to the sustainability of the results.

CONCLUSION

Tunneling is a versatile and secure approach in periodontal plastic surgery. The enlightened use of tuberosity grafts, based on a thorough understanding of their properties and clinical indications, optimizes aesthetic and functional results while minimizing patient discomfort. This surgical approach can be extended to the treatment of peri-implant recessions with additional constraints related to the implant itself.

REFERENCES

- Tavelli L, Barootchi S, Greenwell H, Wang HL. Is a soft tissue graft harvested from the maxillary tuberosity the approach of choice in an isolated site? J Periodontol. 2019;90(8):821-825. doi:10.1002/JPER.18-0615

- Sanz-Martín I, Rojo E, Maldonado E, Stroppa G, Nart J, Sanz M. Structural and histological differences between connective tissue grafts harvested from the lateral palatal mucosa or from the tuberosity area. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23(2):957-964. doi:10.1007/s00784-018-2516-9

- Stuhr S, Nör F, Gayar K, et al. Histological assessment and gene expression analysis of intra-oral soft tissue graft donor sites. J Clin Periodontol. 2023;50(10):1360-1370. doi:10.1111/jcpe.13843

- Jung UW, Um YJ, Choi SH. Histologic observation of soft tissue acquired from maxillary tuberosity area for root coverage. J Periodontol. 2008;79(5):934-940. doi:10.1902/jop.2008.070445

- Karring T, Lang NP, Löe H. The role of gingival connective tissue in determining epithelial differentiation. J Periodontal Res. 1975;10(1):1-11. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.1975.tb00001.x

- Zuhr O, Bäumer D, Hürzeler M. The addition of soft tissue replacement grafts in plastic periodontal and implant surgery: critical elements in design and execution. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41 Suppl 15:S123-142. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12185

- Amin PN, Bissada NF, Ricchetti PA, Silva APB, Demko CA. Tuberosity versus palatal donor sites for soft tissue grafting: A split-mouth clinical study. Quintessence Int. 2018;49(7):589-598. doi:10.3290/j.qi.a40510

- Ronco V. Tunneling : A Comprehensive Concept in Periodontal Plastic Surgery. Quintessence. Quintessence; 2021.

- Sculean A, Allen EP. The Laterally Closed Tunnel for the Treatment of Deep Isolated Mandibular Recessions: Surgical Technique and a Report of 24 Cases. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2018;38(4):479-487. doi:10.11607/prd.3680

- Zadeh HH. Minimally invasive treatment of maxillary anterior gingival recession defects by vestibular incision subperiosteal tunnel access and platelet-derived growth factor BB. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2011;31(6):653-660.